For that: Elements of fracture fixation pdf free download

| YT MUSIC DOWNLOADER AND CONVERTER | |

| RAZER MAN OWAR DRIVER DOWNLOAD | |

| GYPSY 83 HD TORRENT DOWNLOAD | |

| PDF TO JPG FOR MAC FREE DOWNLOAD |

Elements of Fracture Fixation - E-book (eBook)

Bone as Material

Biomechanical Properties of Bone

Tensile Strength and Elasticity

Four Steps of Fracture Healing

Healing of a Treated Fracture

Perren Hypothesis

Healing Process

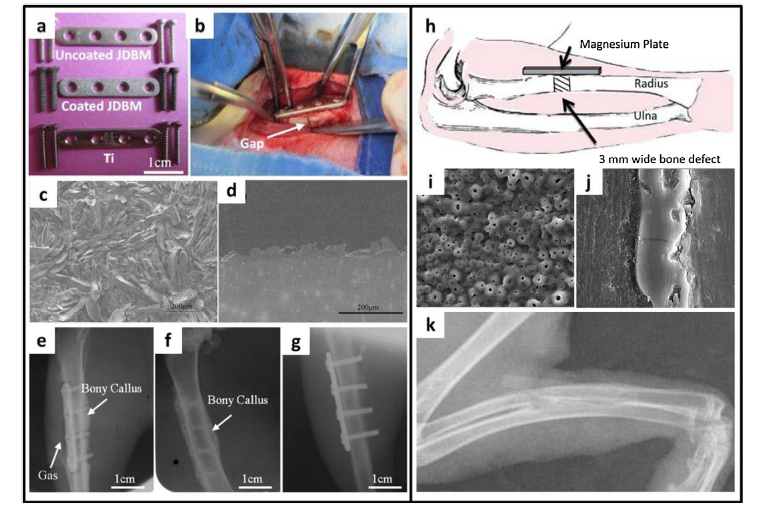

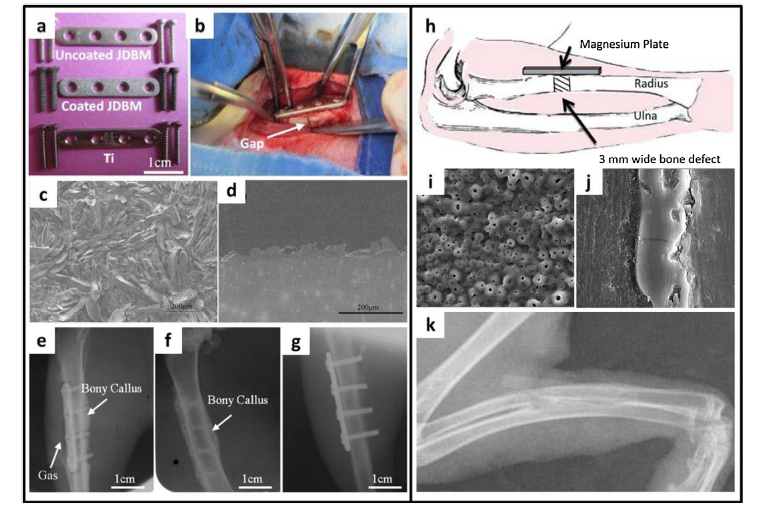

Callus Formation and Internal Fixation

Osteonal and Non Osteonal Healing

Diamond Concept

Conventional Plate and Bone Vascularity

Adverse Clinical Conditions Delaying Bone Healing

Chronic Inflammation

Diabetes

Hypovitaminosis

Ageing

Muscular Mass

Diet, Alcohol and Smoking

Polytrauma

NSAIDs

Enhancement of Bone Healing

Parathyroid Hormone Therapy

Orthobiologics and Tissue Engineering

Natural Bone-Based Bone Graft Substitute

Autogenous Bone Grafts

Bone Marrow

Reamer Irrigator Aspirator

Allogenic Bone Grafts

Demineralized Bone Matrix

Growth Factor-Based Bone Graft Substitutes

BMPs and Other Growth Factors

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) or Autologous Platelet Concentrate

Cell-Based Bone Graft Substitutes

Stem Cells

Collagen

Gene Therapy

Ceramic-Based Bone Graft Substitutes

Calcium Hydroxyapatite and Tricalcium Phosphate (TCP)

β-TCP

Bioactive Glass Ceramices (Bioglass)

Polymer-Based Bone Graft Substitutes

Coral-Based Bone Graft Substitutes

Coralline Hydroxyapatite

Other Modalities to Enhance Bone Healing

Electromagnetic Stimulation

Shock Wave Therapy

Ultrasound

Materials in Fracture Fixation

Metals in Orthopaedic Use

Stainless Steel

Cobalt Chromium Alloys

Titanium Alloys

Comparison of Stainless Steel and Titanium for Fracture Fixation

Shape Memory Alloy

Nickel Titanium Alloy

Polymers

Bioresorbable Polymers

Mechanical Properties

Fracture Fixation

PEEK

Functionally Graded Material

Clinical Relevance

Metal Failure

Metal Removal

Mixing of Implants

Standards Organizations

Metal Working Methods and Their Effects on Implants

Forging

Casting

Rolling and Drawing

Milling

Cold Working

Annealing

Case Hardening

Machining

Broaching

Surface Treatment

Polishing and Passivation

Nitriding

Fabrication of Implants

Corrosion

Galvanic Corrosion

Crevice Corrosion

Pitting Corrosion

Fretting Corrosion

Stress Corrosion

Intergranular Corrosion

Ion Release

Immobilization does not favour the formation of callus, movement does.

– Just Lucas-Championnière, 1910.

Bone as material

Biomechanical properties of bone

Bone is categorized as long bone and flat bone. On macroscopic level, cortical and cancellous types exist, which are described as lamellar and woven bone at microscopic level. Cortical bone exists in 80% of the skeleton. It is made of Haversian systems, which have osteons and Haversian canals; canals contain arterioles, venules, capillaries and nerves. The region between osteons is filled with interstitial lamellae. Cortical bone has slow turnover rate and high Young’s modulus. Cancellous bone is organized as a loose network of bony struts measuring approximately 200 µm. It is porous and contains bone marrow. Newly formed bone is known as ‘woven’ bone and has random arrangement of the tissues. It contains more osteocytes per unit of volume and higher turnover rate compared to lamellar bone. It is also more flexible and weaker than lamellar bone. When it is organized and oriented along the lines of stress, remodelled woven bone is known as lamellar bone. It is stronger and stiffer than the woven bone.

Bone is a composite of type I collagen, ground substance (organic matrix) and calcium and phosphate (inorganic mineral salts). The organic components make the bone hard and rigid whereas the inorganic components give bone its tensile strength and elasticity. Bone is viscoelastic i.e. when loaded at higher rates it is stiffer, stronger and stores more energy. Gross appearance of bone is cortical (compact) and cancellous (porous); both have similar constitution but varying degree of porosity and density. The apparent density of bone is calculated as the mass of bone tissue divided by the volume of the specimen; apparent density of cortical bone is 1.8 g/cm3 while range of apparent density of cancellous bone is from 0.1 g/cm3 to 1.0 g/cm3. After the fifth decade progressive net loss of bone mass occurs, but in women it proceeds at a faster rate. This loss leads to diminished bone strength, a reduced modulus of elasticity and increased possibility of fractures. Nature’s compensatory mechanism initiates remodelling of bone. Bone is absorbed from endosteal location and deposited in subperiosteal zone. This activity leads to an increase in bone diameter and subsequent higher moment of inertia. Thus, thinning of bone is compensated by increased diameter; the transition is smaller in women and predisposes them to an increased rate of fracture.

Tensile strength and elasticity

Bone is formed in two ways. Endochondral bone formation occurs in non-rigid fracture healing (secondary bone healing), longitudinal physeal growth and embryonic long bone formation. Chondrocytes produce cartilage, which is absorbed by osteoclasts. Osteoblasts lay down bone on cartilaginous framework; bone replaces cartilage; cartilage is not converted to bone. Chondrocytes play a significant role in endochondral bone formation throughout the formation of the cartilage intermediate. Intramembranous bone formation is the second method of bone formation, generally known as primary bone healing, contact healing and Haversian remodelling. Fetal bone formation (embryonic flat bones like skull, maxilla, mandible, pelvis, clavicle and subperiosteal surface of long bone) also takes place by intramembranous bone formation. The process is also associated with distraction osteogenesis and fracture healing with rigid fixation, and is a part of healing process in intramedullary nailing. Intramembranous bone formation commences with aggregation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells that later differentiate into osteoblasts; simultaneously organic matrix is deposited.

Four steps of fracture healing

The entire process of diaphyseal fracture healing may be divided into four stages: inflammation, soft callus, hard callus and remodelling. Inflammation starts immediately after the fracture occurs and lasts for 7–10 days. Initial haematoma is gradually replaced by granulation tissue. Osteoclasts remove necrotic tissue from the bone ends. Soft callus is formed in 2–3 weeks after the fracture. Fragments are in a sticky state and there is sufficient stability to prevent shortening, but not angulation. Progenitor cells from the periosteum and endosteum mature to form osteoblasts. Bone growth takes place away from fracture gap and forms a cuff of woven bone at both subperiosteal and endosteal locations. Blood vessels grow into the callus. Mesenchymal cells in the fracture gap proliferate and differentiate into fibroblasts or chondrocytes producing characteristic extracellular matrix. Hard callus develops when the fracture ends are held together by soft callus. The process continues for 3–4 months. Ossification process commences at the periosteum as cartilage is converted into rigid calcified tissue by endochondral ossification. Thus, bony callus growth begins in the peripheral areas and slowly progress towards the gap. Osseous bridge is formed away from the cortex, either externally or in the medullary canal. Finally, through endochondral ossification, the soft tissue in the gap is converted. The fourth stage of remodelling commences after hard callus is well established. The osteoclasts ream out a tunnel in the dead cortical bone down that a blood vessel follows, bringing in the osteoblasts that lay down the lamellar bone. If the fractured bone ends...

-